The Orbital Servicing Wars - Part I: A Brief History till Date

Drawing out the distinct approaches taken by China, the US and Europe in pursuing on-orbit servicing over the past 15 years.

A. Happening Now in GEO

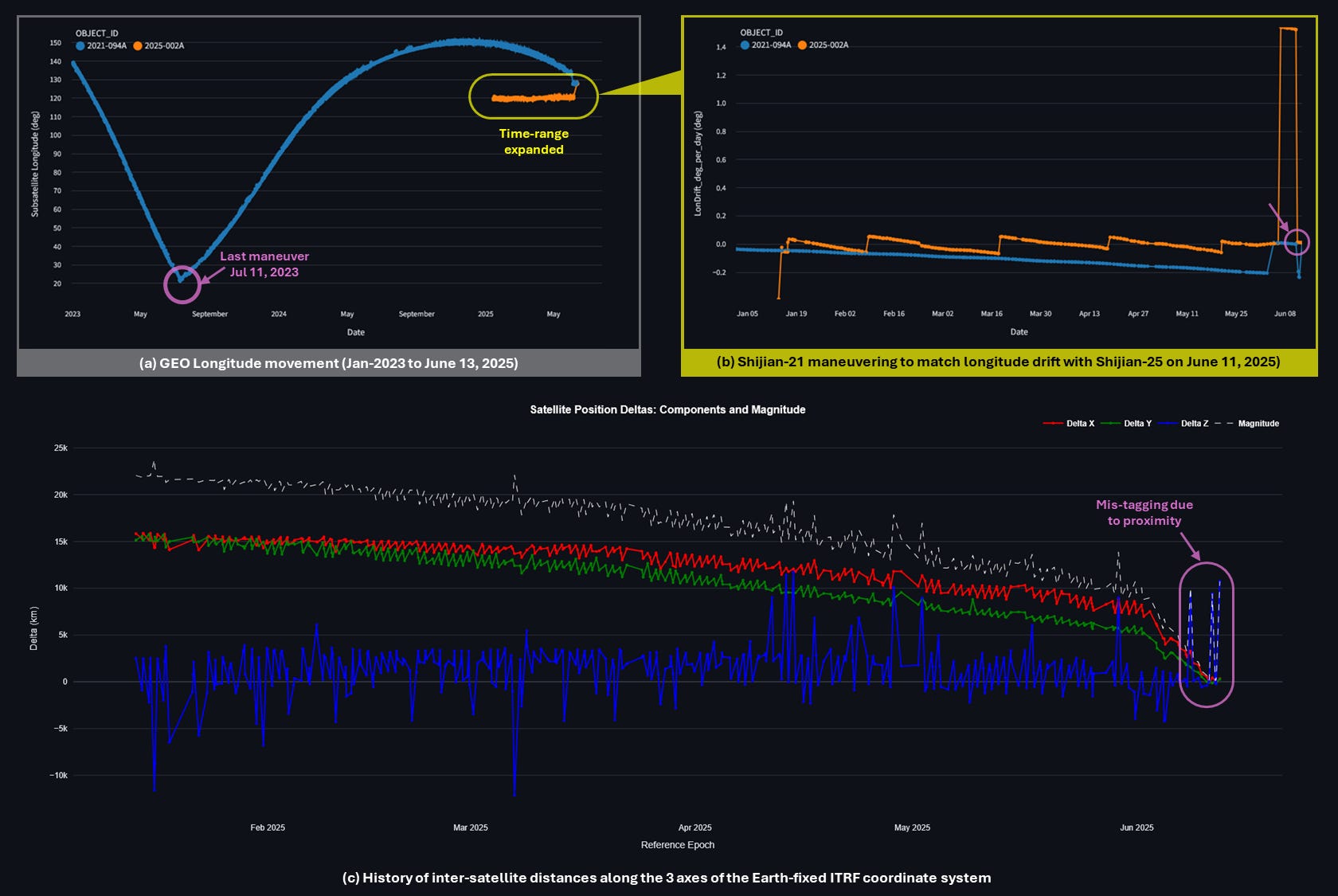

As of date, approximately 35,800 kilometers above Earth in geostationary orbit, China's Shijian-21 (49330/2021-094A) satellite maneuvers toward Shijian-25 (62485/2025-002A) in what will be China's first operational satellite refueling mission. Launched in January 2025 for explicit "satellite fuel replenishment and life extension service technology verification," Shijian-25 is being approached by a spacecraft that previously demonstrated sophisticated debris removal capabilities. This represents China's systematic development of space servicing as a strategic capability, moving beyond experimental demonstrations to operational deployment.

Simultaneously, commercial space servicing is demonstrating proven repeatability. Northrop Grumman's Mission Extension Vehicle-1 (MEV-1), having completed its life extension contract with Intelsat 901, is now approaching Australian satellite Optus D3 for another commercial servicing mission. MEV-1 undocked from Intelsat 901 after depositing it in a graveyard orbit 400km beyond the GEO belt on April 9th, 2025, and immediately repositioned for its next client. This operational cycle proves the commercial viability and technical repeatability of autonomous satellite servicing, establishing the foundation for broader applications.

MEV-1's success in 2019 was just the beginning of what we now recognize as the in-space servicing revolution - encompassing satellite inspection, refueling, life extension, last-mile orbital delivery, and controlled de-orbit services. Following MEV-1's breakthrough, MEV-2 launched in August 2020 and successfully docked with Intelsat 10-02 in April 2021, this time while the target satellite remained fully operational. The viability of satellite servicing was no longer theoretical - Intelsat was a repeat customer.

The convergence of these parallel developments marks a critical inflection point. What began as solutions to straightforward problems (extending profitable satellite life and removing space debris) has evolved into foundational infrastructure for space power projection. Both commercial operators and strategic competitors now recognize that the ability to maintain, repair, refuel, and reposition satellites in orbit represents critical capability for sustained space operations.

The transformation from experimental concept to operational reality has exposed fundamental questions about the relationship between commercial innovation and military advantage. While companies like Northrop Grumman are proving technical feasibility through market success, the applications of these technologies and the policies governing their development remain contested across major space powers. Understanding this tension has become essential to comprehending the infrastructure requirements that will determine a space power’s advantage in space operations.

B. Industry Timeline: The Commercial Foundation

The transformation of in-space servicing from experimental concept to strategic need can be traced through a series of developments that reveal how commercial innovation has shaped and reshaped institutional thought. Make no mistake, the journey till here has neither been short on struggles, nor drama.

Before 2016: The Beautiful Letdown

Early attempts at commercial satellite servicing revealed the gap between technical possibility and market reality. Canada's MDA Corp. and Intelsat's 2011 agreement to develop the Space Infrastructure Services (SIS) vehicle collapsed by 2012 despite a $280 million investment commitment. Intelsat withdrew citing lack of US Department of Defense interest, while Air Force officials deemed the price too steep for fleets already financed for replacement. The fundamental challenge was clear: satellite servicing required both technical breakthrough and sustainable business model. This early failure established the template for subsequent commercial development, where technical capability alone proved insufficient without clear value proposition and committed customers.

2016-2020: Breakthrough Proof of Concept

Three distinct approaches emerged as satellite servicing transitioned from concept to reality. Northrop Grumman (then Orbital ATK) succeeded where others failed by securing Intelsat as an anchor customer for its MEV (then Gemini) platform in 2016, focusing on extending profitable operational life of existing commercial satellites. Simultaneously, Europe pursued systematic institutional development: ESA upgraded its e.Deorbit program (instituted in 2013 for active debris removal) to comprehensive in-orbit servicing, eventually selecting ClearSpace to demonstrate capabilities with PROBA-1 as the target satellite.

Meanwhile, regulatory and competitive battles illustrated the complex relationship between government research and commercial development. MDA's subsidiary Space Systems Loral nearly received $15 million from DARPA in 2017, prompting Orbital ATK to sue over duplicated taxpayer investment. The lawsuit's dismissal and DARPA's subsequent RSGS program launch showed how some nations were pursuing parallel development paths.

DARPA’s RSGS program was not created in a vacuum nor without precedent. Way back in 2007, DARPA executed the Orbital Express mission aimed at "a safe and cost-effective approach to autonomously service satellites in orbit". Despite proposing follow-up programs like SUMO, FREN and Phoenix (to repurpose a dead satellite’s parts to create zombie satlets), there was no real hardware put in space after that. DARPA, from the time of Orbital Express (and the NASA-CSA Robotic Refueling Missions), had involved private contractors - who have, always, looked to bring all that experience back into the market as commercial offerings. Northrop and MDA have been in play, ever since.

The technical validation came in February 2020 when MEV-1 successfully docked with Intelsat 901, proving autonomous satellite servicing was operationally viable. This achievement coincided with broader industry recognition: Japan's Astroscale raised $50 million and secured JAXA's debris removal demonstration, while the US Defense Innovation Unit released solicitations for four distinct on-orbit services.

The RemoveDEBRIS mission, led by Surrey Satellite Technology Ltd (SSTL) with EU and ESA support, was launched in 2018 and deployed from the ISS. It tested net capture, harpoon targeting, vision-based navigation, and a dragsail for deorbiting - validating methods for capturing and disposing of non-cooperative targets in space.

The convergence of American commercial success, European institutional commitment, and Asian competitive entry established 2020 as the year satellite servicing transitioned from experimental to operational technology.

Following MEV-1’s successful demonstration, DARPA decided to give the RSGS program one more try by signing up Northrop the very next month, armed with an expanded budget of $64.6 million for the year 2020.

2021-2022: Market, International Activity & Strategic Recognition

Commercial validation accelerated interest across regions. MEV-2's April 2021 success with Intelsat 10-02 demonstrated repeatability, while Orbit Fab and Astroscale's January 2022 fuel supply agreement created the first integrated commercial supply chain. Europe advanced through institutional pathways: ClearSpace signed a life-extension deal with Intelsat, demonstrating European entry into the growing GEO servicing market alongside their debris removal focus.

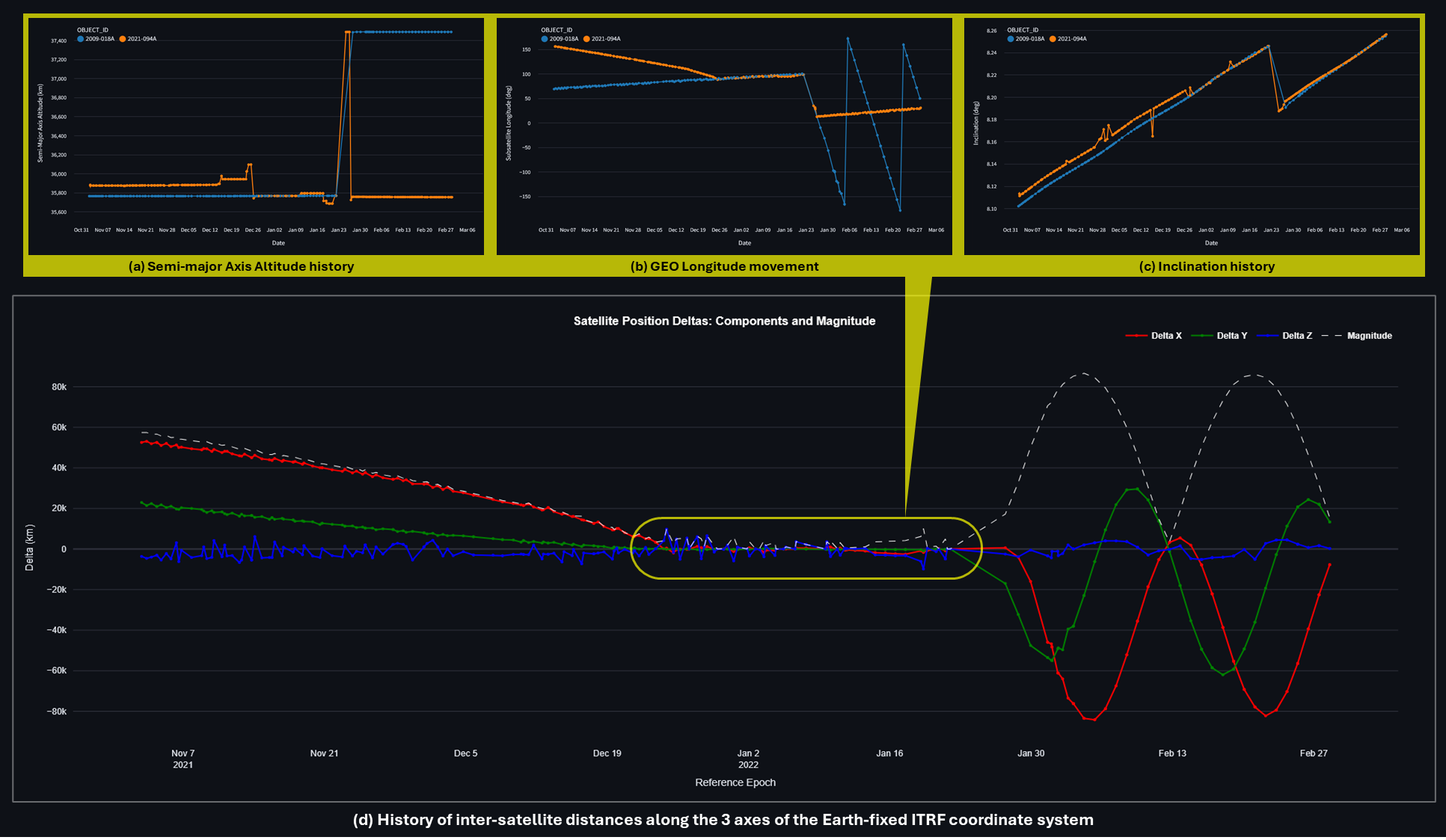

The international landscape shifted dramatically in January 2022 when China's Shijian-21 demonstrated sophisticated debris removal by towing the defunct BeiDou-2 G2 navigation satellite to graveyard orbit. Unlike Western commercial missions focused on extending profitable satellite life or European debris removal demonstrations, Shijian-21's disposal of a strategic navigation asset showcased space servicing as sovereign capability for protecting national space infrastructure. This demonstration revealed that technical capabilities developed through different pathways could be adapted rapidly for strategic purposes.

2023: US Military Interest and European Consolidation

US military engagement intensified as policy implications became apparent. The Space Force and Astroscale announced co-investment in refueling satellite development, with $25.5 million of congressional funding supporting demonstration missions. Orbit Fab's $28.5 million Series A funding and $12 million in defense contracts illustrated the dual-use nature of servicing technologies.

European activities consolidated around systematic institutional approaches. The UK Space Agency allocated £15 million for in-orbit servicing and manufacturing (ISAM) research, shortlisting international consortia led by Astroscale (partnered with Canada's MDA) and ClearSpace (with Swiss leadership). ClearSpace raised €29 million in 2023, bringing total funding to €130 million from government and commercial sources. This European model emphasized multilateral partnerships and institutional stability over rapid commercial deployment, creating a third pathway distinct from US market-driven and Chinese state-directed approaches.

2024: Policy Confusion

Despite technical progress and international competition, US policy signals became contradictory. The Space Force simultaneously funded experiments while demanding industry "prove value," creating uncertainty about military commitment. This confusion persisted despite commercial viability evidence and China's operational demonstrations.

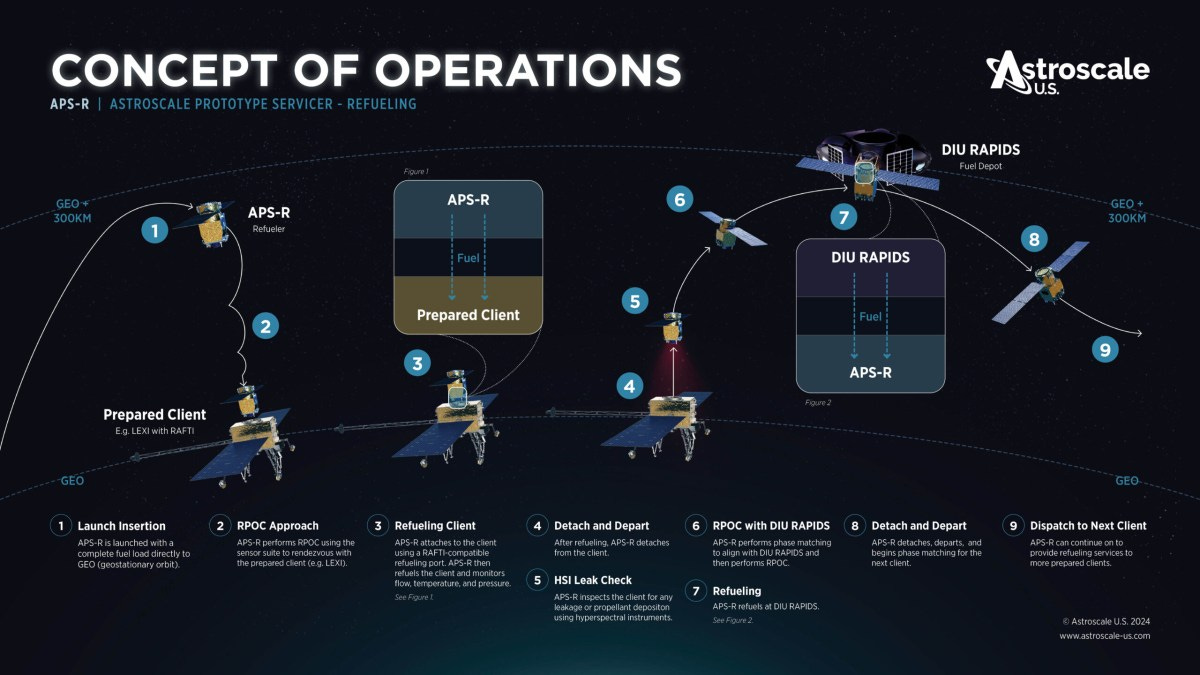

European approaches showed greater institutional consistency. D-Orbit raised €150 million and entered the GEO servicing market, while ESA selected OHB to take over leadership of the ClearSpace-1 mission toward "a more expedited and cost-effective approach." The European model may be seen as an institutional framework that is adapting to realities while maintaining strategic coherence. Meanwhile, the newly created US DOD Assured Access to Space program awarded $37.5 million to Starfish Space for GEO servicing by 2026, suggesting continued policy experimentation rather than systematic capability development. Probably the first architectural plan shown to the public was when Astroscale unveiled the ConOps for its APS-R mission, calling out the high-level activities required for any in-space refueling operation.

2025: The Inflection Point?

China

China's launch of Shijian-25 in January this year for explicit "satellite fuel replenishment and life extension service technology verification" eliminated ambiguity about strategic intent. Unlike previous missions interpretable as debris removal or scientific experiments, Shijian-25's stated mission directly paralleled commercial capabilities for strategic purposes.

United States

Commercial success has not translated into policy coherence. Despite MEV's proven capabilities and China's operational demonstrations, US military leadership exhibits what industry observers describe as "brown water vs. blue water" identity confusion. Lt. Gen. Shawn Bratton's statements that "I don't know that I see the clear military advantage of refueling" exemplify this uncertainty.

The "brown water" defensive mindset may explain this confusion. Like littoral combat ships operating near friendly ports, a defensive space force might not prioritize capabilities that enable sustained operations far from Earth. This contrasts sharply with "blue water" thinking that emphasizes power projection and persistent presence across operational domains.

Policy implementation reflects this uncertainty: simultaneous funding of experiments and demands that industry "prove value" suggest continued debate about military requirements. The Space Force's approach treats space servicing as experimental capability requiring validation rather than foundational infrastructure requiring systematic development.

Europe

Despite over a decade of institutional commitment and substantial funding allocation, European efforts have not achieved in-orbit demonstration of space servicing capabilities. While US and Chinese programs complete operational missions, European programs remain in development phases with key demonstrations still pending execution. This institutional thoroughness creates stability and shared risk but suggests that coordination may sacrifice operational urgency for procedural completeness, raising questions about whether deliberate consensus-building will eventually produce more robust capabilities or fall permanently behind operational competitors.

The question for 2025 is whether these divergent approaches will compete or complement each other, and which model proves most effective for sustained space operations in an increasingly contested environment.

C. China's Integrated Development Model

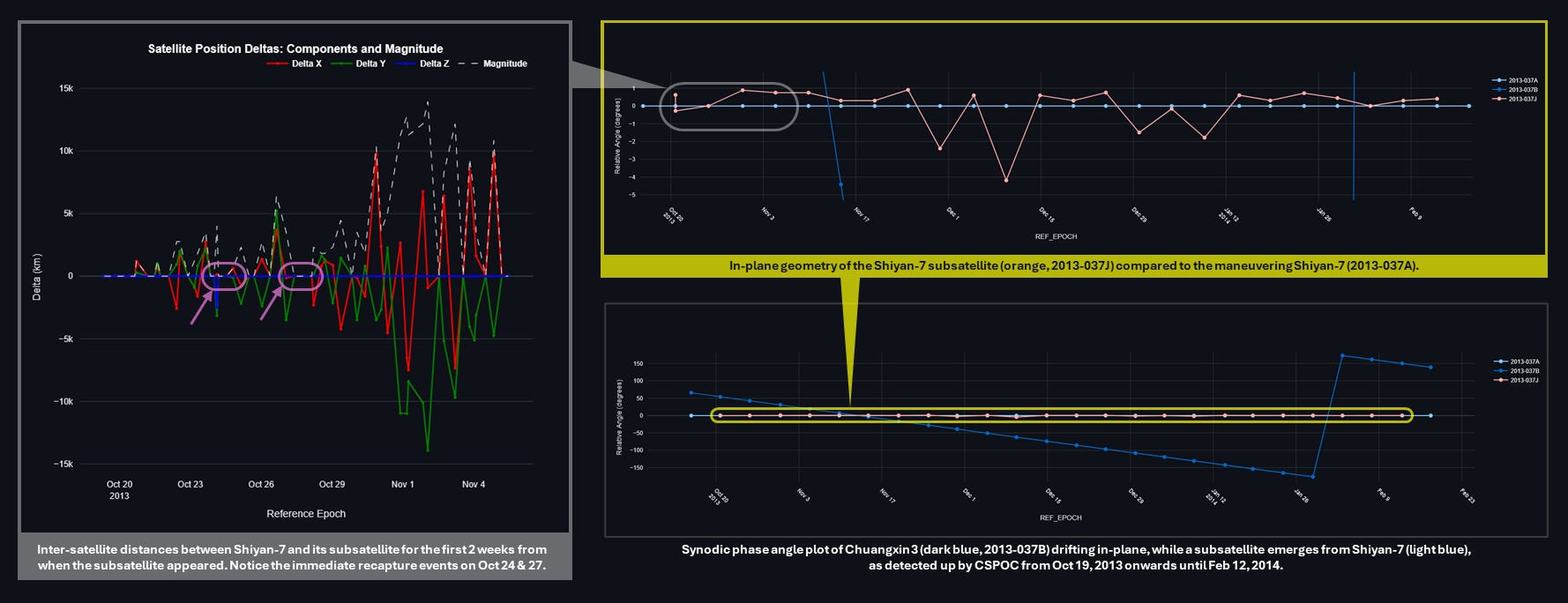

China's approach to space servicing demonstrates systematic integration of experimental capabilities toward operational goals. Beginning with Shiyan-7's subsatellite deployment and manipulation in 2013, Chinese missions have followed a deliberate progression through multiple orbital regimes and increasing technical complexity.

The LEO proving ground established foundational capabilities: Shiyan-7's robotic arm operation (2013)s, Tianyun 1's in-orbit fuel transfer demonstration (2016), and Ao Long 1's debris capture experiments. These missions validated core technologies while developing operational procedures for proximity operations and mechanical manipulation.

Human spaceflight and lunar programs provided crucial technology transfer pathways. China Academy of Space Technology (CAST) developed automated docking systems requiring relative position control accuracy below 10 centimeters, demonstrated successfully in Chang'e 5's lunar orbit rendezvous (2020) and repeated in Chang'e 6 (2024). Shanghai Academy of Spaceflight Technology (SAST) created parallel pathways through Tiangong space station robotic arms and Shijian-25 development.

GEO operations escalated technical and geopolitical stakes. Shijian-17 (2016) became "the first Chinese satellite to bear a robotic arm" in geostationary orbit, performing unexplained maneuvers including temporary 4° inclination changes. TJS-3 (2018) deployed a subsatellite and conducted proximity inspection operations, including approaches within 6 kilometers of American military satellites USA 233 and USA 298.

Shijian-21's January 2022 debris removal demonstration and Shijian-25's explicit refueling mission represent operational deployment of integrated capabilities. This progression reveals strategic planning that treats space servicing as foundational infrastructure for sustained space operations rather than discrete commercial services.

Architectures and Operational Sophistication

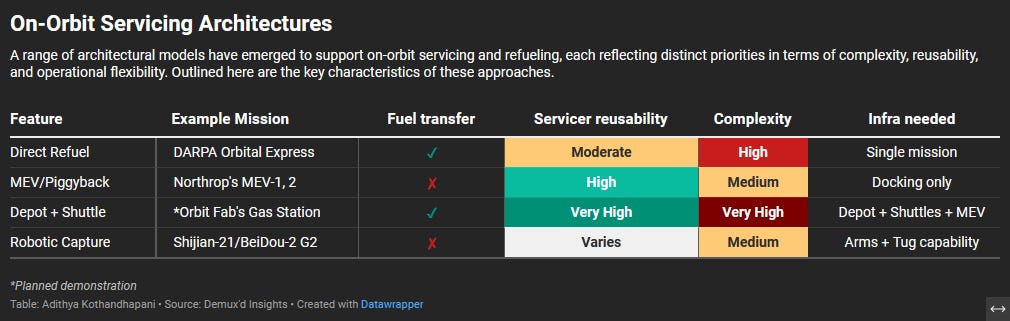

China's technical choices reveal a positioning between more conventional servicing architectures. Rather than adopting purely commercial approaches (like MEV's life extension focus) or depot-based models (like proposed fuel stations), China has developed what can be termed a "MEV-refueler" hybrid model. This approach combines high servicer reuse with moderate complexity and flexible life-extension capabilities, positioned between the "Depot + Shuttle" and "MEV/Piggyback" ends of the servicing spectrum as laid out in the table below.

Over multiple missions, Chinese satellites have been seen to be entering and exiting graveyard orbit regions for rapid longitudinal repositioning, maneuvers that could be dismissed as innovative orbital mechanics but serve operational purposes when combined with proximity operations capabilities. This technical sophistication creates deliberate operational ambiguity, allowing some of their activities to appear as routine orbital maintenance or debris management. The key, though, is that there is a space power that is deliberately putting in operational hours in new regimes and mission profiles - thereby knowing what works and what doesn’t. This is more valuable that any number of PowerPoint presentations, contract awards, or bluster!

D. Implications of Divergent Approaches

Each of the different philosophies create distinct advantages and vulnerabilities. More fundamentally, these approaches reflect different assumptions about space competition itself. China's systematic development suggests preparation for sustained competition across multiple orbital regimes, while other powers seem to hope that market mechanisms will generate strategic capabilities when needed.

The convergence of these models in 2025 creates an unprecedented situation: similar technical capabilities developed through fundamentally different philosophies now compete directly. The question is not which approach generates superior technology, but which philosophy proves most effective for sustained space operations in an increasingly contested environment where the rules of competition remain contested and evolving.

While technical feasibility is no longer in question, the critical challenge facing all spacefaring nations is understanding how different servicing approaches create advantages and vulnerabilities in an increasingly contested space environment. Part II will examine these trade-offs through a systematic framework, analyzing how technical choices about satellite servicing translate into national competitive positions and why conventional approaches to space logistics may be inadequate for the emerging international landscape.

Spot on analysis of that entire period. About the only thing missing is that a significant player in the ability of commercial providers to "prove value" was that the private equity market in the US froze absolutely solid in late 2022 through most of 2024. There was no way for those companies to take the risk of demonstrating capability if the Space Force was unwilling to commit to anything if they did.

All of this is a general misunderstanding of China's goal. China firmly believes that it can attain all of its objectives without ever firing a shot by simply outcompeting its near-peer adversaries economically.